In a right-to-work state, private-sector employees have the option to choose whether or not they want to join a union. In other states, a person applying for a private-sector job where employees are unionized can be required to join the union as a requirement of being hired.

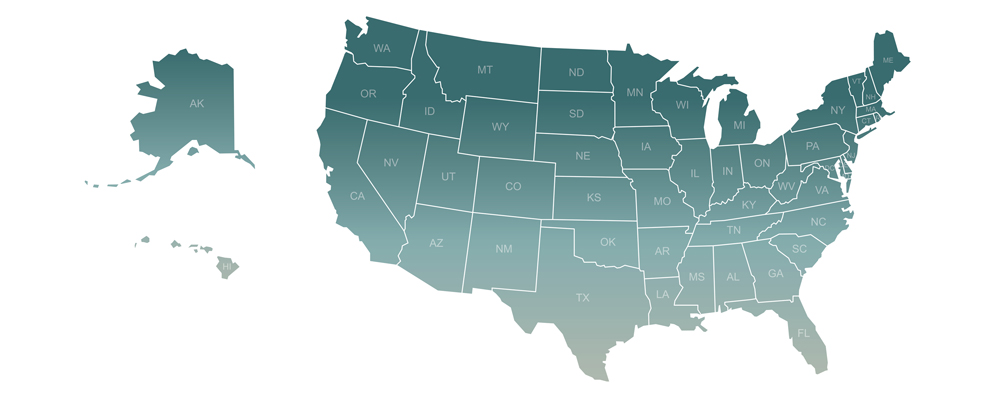

Right-to-work laws do not prevent unions from forming or negotiating contracts, but they do prohibit mandatory union membership and dues. More than half of U.S. states have right-to-work laws, while others allow unions to require dues from all employees covered by a union contract.

With regard to public-sector employees, a Supreme Court ruling in 2018 essentially made every state a right-to-work state for public-sector unions. The Janus v. AFSCME decision determined that government employees cannot be required to pay union dues or fees, even if they benefit from union representation. This ruling overturned prior state laws that allowed unions to collect fees from non-members and significantly changed how public-sector unions operate across the country.

Understanding Right-to-Work Laws

The idea behind right-to-work laws goes back to the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, which gave employees the right to form and join unions. This law was a turning point for American workers as it protected their ability to organize and bargain collectively. But it also introduced a debate over whether workers in unionized workplaces should be required to join the union or pay dues.

That’s when some states passed right-to-work laws to make sure that employees had a choice to join the union and pay dues or to opt out without risking their jobs. Supporters saw these laws as a way to protect individual freedoms, and opponents argued they made it harder for unions to negotiate better pay and benefits. The debate continues today, with businesses, lawmakers, and workers often split on whether right-to-work laws help or hurt the workforce.

In summary, right-to-work laws affect union membership and dues, not broader workplace protections. They don’t prevent unions from forming, nor do they eliminate collective bargaining agreements. They do allow employees to opt out of union membership and dues payments, even if they still benefit from union-negotiated contracts. That means businesses need to understand different state labor rules, especially when they operate across right-to-work and non-right-to-work states.

Right-to-Work Laws in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina

- Maryland: Maryland is not a right-to-work state, meaning employees in unionized workplaces can be required to join a union or pay dues. In 2024, 11.4% of wage and salary workers in Maryland were union members, a rate higher than both Virginia and North Carolina.

- Virginia: Virginia is a right-to-work state and has maintained its law despite legislative discussions around labor reforms. The state’s union membership rate stood at 5.2% in 2024, below the national average of 9.9%.

- North Carolina: North Carolina is a right-to-work state and has the lowest union membership rate in the country at 2.4% in 2024. The state has historically maintained strong right-to-work policies with little movement toward changing them.

(From the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2025)

Right-to-Work vs. At-Will Employment

The terms “right-to-work” and “at-will employment” are often used interchangeably, but they mean very different things.

- At-will employment means an employer can terminate an employee at any time, for any lawful reason, and an employee can leave a job without notice. This applies to most private-sector workers except those covered by a union contract or an individual employment agreement.

- Contract employment is the opposite of at-will employment. In this case, an employee works under a formal contract that outlines job duties, pay, benefits, and employment terms. Unionized employees fall into this category because their working conditions are covered by a collective bargaining agreement between the union and the employer.

Where does right-to-work fit in? Right-to-work laws do not affect at-will employment. Instead, they only determine whether an employee in a unionized workplace is required to join the union or pay dues. Even in right-to-work states, employees who opt out of union membership are still covered by the union’s contract if they work in a unionized job.

Simply put, right-to-work laws affect union membership requirements, not whether an employee is at-will or contract-based.

What to Watch

The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act was first introduced in 2021, and it was reintroduced in 2023. It sought to eliminate state right-to-work laws and require all represented employees to pay union dues. But after years of debate, the bill has stalled, and as of early 2025, there’s no sign of movement in Congress.

At the state level, there’s been plenty of discussion but not much action. Some lawmakers want to strengthen right-to-work protections, while others are pushing to repeal them altogether. So far, though, no major changes have passed in Maryland, Virginia, or North Carolina. For now, right-to-work remains a state-by-state issue.

Even without new laws, unionization efforts are gaining momentum. More than 400 Starbucks stores unionized in 2023, and there were recently major contract wins for the UAW (United Auto Workers). Public opinion is shifting, too. A 2023 Gallup poll found that 67% of Americans approve of unions, which is the highest percentage in over 50 years. Among younger workers, support is even stronger, with a majority of Americans under 30 having a favorable view of unions.

What does this mean for businesses? Right-to-work laws aren’t changing, but workplace attitudes might be. More organizing efforts could be on the horizon, especially in industries with younger workforces. Regardless, employers will want to monitor state labor policies and ensure compliance across jurisdictions. For more information on how right-to-work laws affect your unique situation, contact your PBMares accounting professional.